HSTP NEW TEST ►

HSTP - Hoshangabad Science Teaching Programme

The HSTP story began in early 1972, when a group of scientists, engineers, educationists and social activists formulated a vision of developing a model of school science teaching close to the ideal envisaged in various policy directives. The Department of Education, Government of Madhya Pradesh, permitted two non-governmental organisations, Friends Rural Centre (FRC), Rasulia, and Kishore Bharati (KB) to take up a pilot project in May 1972 in 16 middle schools spread over two blocks of Hoshangabad district.

The main objective of the project, which came to be known as the HSTP (Hoshangabad Science Teaching Programme), was to explore the extent to which innovative changes can be introduced within the framework of the government school system. To test this hypothesis, the HSTP undertook to investigate whether it would be feasible to introduce the ‘discovery’ approach to learning science in village schools in place of the traditional textbook-centred ‘learning by rote’ methodology. In course of time, the concept of environment-based education was included as an integral part of science teaching.

A basic assumption behind this effort was that learning science through experiments and field studies would help build up a questioning and analytical attitude in children. Since the programme also emphasised learning directly from the local environment, it was hoped that the children would eventually begin to question the traditional social structure of their village society.

The Madhya Pradesh education department played a special role in this nascent effort by giving administrative backing and academic freedom to experiment with books, kit, curricula, teacher training and examinations. This freedom allowed the HSTP to address innovation and quality improvement in science education as an integrated whole, focusing on all aspects of school functioning to facilitate innovative teaching. This unique instance of a state government accepting the role of a voluntary agency in changing school education within its own framework was a landmark in education in the country, enabling the HSTP to evolve as a model for innovative quality improvement in the mainstream education system on a macro scale.

The programme was academically guided through the active involvement of young scientists, educators and research students from some of the leading academic and research institutions in the country. The initial impetus was given by groups from the All-India Science Teachers Association (Physics Study Group) and Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), Mumbai. They were joined in 1973 by a group from the University of Delhi, which went on to take over the academic responsibility for the programme. Other institutions of repute that contributed to the effort included the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), various universities and post-graduate colleges.

The University Grants Commission (UGC) granted fellowships to faculty members from Delhi University and other academic institutions to participate in the programme at the field level while the Madhya Pradesh government also permitted its college science teachers to interact on a regular basis from 1975. This synergy between the university community and school science teachers in developing academically sound curricular materials for village schools was also a unique feature of the programme.

To learn more about HSTP, click on the links below:

Bibliography of HSTP Documents

Page created by Asha Columbia during debate around HSTP Closure in 2002

(Extensive documentation of the history of HSTP, academic documents. articles and other documents)

New Beginnings - A Three Year report of Eklavya Foundation (2001-2004)

Anuvartan Report(1976-1977)

One of the reasons why the innovative science education programme running in Bombay’s municipal schools was closed down was because the municipality refused to permit any changes being made in the Board examinations. It was clear to the teachers that their students would not be evaluated for the kind of things they were learning in science because the Board examinations only ask questions about formulae and memorized information. So their students would be at a disadvantage and would suffer.

from Jashn-e-Taleem

1972: Government approves proposal for innovation in science education in 16 middle schools submitted by Kishore Bharati (KB), Bankhedi, and Friends Rural Centre (FRC), Rasulia. Programme begins with support from the All India Science Teachers Association (AISTA). First teacher training camp held in May. First edition of the Bal Vaigyanik published in September.

1973: The Science Education Group of Delhi University (DU) joins the programme. The University Grants Commission (UGC) extends official approval for their participation.

1975: The Science Teachers Group from colleges of Madhya Pradesh joins the programme. After three years of effort, chapters of the Bal Vaigyanik workbooks for Class 6, 7 and 8 are published as card sheets. UGC announces fellowships for volunteers participating in the programme.

The government grants permission for making changes in the examination system. First batch of children sit for the Class 8 Board examination, conducted by KB and FRC.

1977: Joint decision by the Education Department, Government of Madhya Pradesh, and the National Council for Educational Research and Training (NCERT) to expand the HSTP to all the middle schools in Hoshangabad district. The Regional College of Education (RCE) coordinates preparation of detailed proposal for district-level expansion. The Bal Vaigyanik curriculum and workbooks approved by the State Textbook Review Committee.

1978: District-level expansion takes place. The Madhya Pradesh Textbook Corporation (MP-TBC) begins publication of the Bal Vaigyanik. Administrative Committee with Director, Public Instruction (DPI) as chairman set up and Science Cell established in the District Education Office (DEO), Narmada Division, to administer the programme.

1982: Formation of Eklavya. State Council for Education Research and Training (SCERT) established. Deputation of government teachers to HSTP begins.

1984: Seeding of programme under auspices of SCERT in three districts through school complex route as model for state-level expansion: Ujjain (Narwar complex), Dewas (Hat Pipalya complex) and Dhar (Tirla complex).

1985: Seeding in three more districts: Shajapur (Agar complex), Mandsaur (Pipliya Mandi complex) and Ratlam (Namli complex).

1986: Seeding in six more districts: Narsinghpur (Gotegaon complex), Chhindwara (Parasia complex), Khandwa (Harsud complex), Indore (Sanwer complex), Jhabua (Meghnagar complex) and Khargone (Mandleshwar complex).

1987-89: First revision of the Bal Vaigyanik begins, based on feedback from schools.

1990: Eklavya submits proposal for state-level expansion of the HSTP to the Madhya Pradesh government and the Ministry for Human Resources Development (MHRD), Government of India. The NCERT sets up six-member expert committee under the chairmanship of Prof. B. Ganguly to review the programme.

1991: The Ganguli committee submits its report. Appreciating the programme, it recommends its phased expansion across the state.

Planning for state-level expansion begins but a change in government derails the process. New government calls for fresh review of the HSTP and sets up expert committee under the chairmanship of Dr G.N. Mishra, Director, State Institute for Science Education.

1992: The Mishra committee presents a favourable report but for undisclosed reasons the report is never released nor made public.

1993: Five institutions in Gujarat join hands, get government approval, and launch a Learner Centred (Adhyaita Kendri)Science Teaching Programme, based on the HSTP methodology, in three districts of the state.

1994: State-level expansion of the HSTP again on the agenda. The government sets up new committee under the chairmanship of Director, SCERT, to formulate expansion plan. Committee postpones work on the plan, citing SCERTs preoccupation with the District Primary Education Programme (DPEP).

Work on second revision of the Bal Vaigyanik begins but is kept on hold.

1995: Resource teacher training workshops begin.

Kit replacement streamlined by levy of a science cess on all middle schools in the state to meet the expenditure.

1996: Decentralised teacher training model adopted to address problems of private schools and facilitate participation of resource teachers.

1998: English edition of the Bal Vaigyanik published.

Lok Jumbish Parishad seeds the programme in Rajasthan and publishes workbooks titled Khojbeen.

1999: Bal Vaigyanik revision, on hold since 1994, taken up again. Teachers participate on a mass scale to field test material with the children.

2000: Revised edition of the Class 6 Bal Vaigyanik published after approval by the Madhya Pradesh Textbook Standing Committee.

Discussions on state-level expansion renewed.

2001: Revised edition of the Class 7 Bal Vaigyanik published.

Rewriting/revision of the Class 8 Bal Vaigyanik begins.

2002: Government decides to shut down the programme. Revised edition of the Class 8 Bal Vaigyanik remains unpublished.

The magazine was visualized as an in-house journal of the HSTP where the teachers could link up with each other to exchange ideas and information. Its publication began in 1980, five years after the district level expansion, and the HSTP group had to put in a lot of effort to ensure it came out regularly.

A SINGULAR INITIATIVE

July 3, 2002 was a dark day in the history of education. It was on this day that the Madhya Pradesh government decided to draw the curtains on an innovative educational programme known the world over as the Hoshangabad Science Teaching Programme (HSTP). The state government’s ill-conceived move did not come as a surprise to those conversant with the processes of privatization and globalization, their analysis of its root causes pointing to its inevitability.

The HSTP initiative began as a small experiment in 1972. Anecdotal lore tells the story of two voluntary organizations – Friends Rural Centre (FRC) and Kishore Bharati (KB) - approaching the Madhya Pradesh government to seek permission to conduct an exploration in science education in its state-run middle schools. Setting aside any possible objections to giving the required approval, the then Director of Public Instruction, Dr B.D. Sharma famously observed, “The present state of science education in these schools is so deplorable that these novices cannot possibly make it any worse. So I see no reason to deny them permission.” This tongue-in-cheek – but insightful - observation of a bureaucrat with his heart in the right place paved the way for a remarkable adventure in school science education.

The forum newly created by these two voluntary organizations quickly drew scientists from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) in Mumbai, members of the All India Science Teachers’ Association (AISTA), and academic staff from Delhi University (DU) to join hands with the teachers of 16 middle schools in the Hoshangabad district of Madhya Pradesh to embark on a journey to make education, in particular science education, a meaningful and joyful experience for school children. It drew countless participants along the way as it evolved, attracting scholars, teachers and scientists from colleges, universities and research institutions across the country.

This was, perhaps, the HSTP’s most significant feature. It provided a platform in the field of education where the creative energies of an entire nation could be unleashed. It was a collective effort to improve science education in schools in which professors and students from colleges and universities, scientists and research scholars from research establishments, school teachers, artisans and craftsmen, farmers, social activists, engineers, doctors, educationists, etc, participated.

Its second important feature was that it showed that teaching-learning in the classroom is not an individual enterprise but a collective process in which every participant is actively involved. It is also a joyful experience, the constant interaction ensuring there is never a dull moment for the students, teachers and others. The environment it created was of shared joy that bound the participants together. It attracted new entrants down the years, encouraging them to contribute their best and giving them the courage to try out new ideas in education. This is why the HSTP was always able to retain a measure of freshness and vitality throughout its 30-year history.

One other aspect also needs to be considered. The HSTP process may have been fun, but it did not lack in educational rigour, with zero tolerance for laxity in analysis, research and implementation. The task on hand could be writing a chapter, trying out an experiment, ensuring the authenticity of a diagram, teacher training or even proof-reading the Bal Vaigyanik, compromises on quality were never part of the equation.

Discovery and the environment

The HSTP was a discovery and environment-based innovation in which children interacted with their environment, conducted experiments, arrived at a hypothesis based on their observations, and then tested their hypothesis. It was, perhaps, for the very first time in the country that children in middle schools learnt scientific concepts by conducting experiments in groups, going on field trips, recording their observations and then analyzing their tabulated data to derive their conclusions. Their teacher was their guide and companion in the process. And the children enjoyed doing all this, quite literally throwing the traditional method of rote learning out of the window.

The HSTP group emphasized the fun aspect of learning, which was later incorporated into the mainstream education lexicon as the ‘Joy of Learning’. When resource person Panchapakesan was asked to list the learnings from the HSTP following its closure, he answered with little hesitation, “We enjoyed ourselves. The teachers enjoyed themselves. The children enjoyed themselves. What more do you want?”

But ‘fun and enjoyment’, apparently, wasn’t considered a component of learning by the bureaucracy. Submitting a report recommending that the HSTP be shut down, a senior bureaucrat of the Madhya Pradesh education department dismissed the innovation as being without merit, scarcely disguising his sarcasm as he wrote, “The only remaining argument in its favour is the ‘enjoyment of the children’, which is an intangible and inadequate index of the quality of learning.”

Stated briefly, the HSTP sought to structure the curriculum around ‘science by doing’, around developing an understanding of scientific concepts rather than incorporating the explosion of scientific facts and information in textbooks. Its guiding principle was that the children learn scientific laws, definitions and concepts not by memorising them but by conducting experiments, tabulating and analysing their observations and data and engaging in group discussions in the classroom.

The essence of the programme was its emphasis on self learning by the children. To equip them for the task, it sought to familiarize them with methods and activities that would help them seek answers to new questions and problems they constantly confront.

The HSTP experiment entered its second phase in 1975, when it was scaled up to all the middle schools in Hoshangabad district following intensive field testing in its pilot phase in 16 middle schools.

At the time the state government took the ill-fated decision to close down the programme, the HSTP was operative in over 800 schools spread over 15 districts of the state. The population of students who had studied science using its methodology over the 30 years of its existence numbered over 250,000. More than 3,000 teachers were involved in its implementation, having undergone a series of remarkable trainings whose depth and rigour can only be appreciated through actual experience. A core group of around 200 resource teachers who could train teachers and organise large-scale trainings was another of its contributions. Many of these have taken a leading role in conducting teacher training camps in other states.

The HSTP set a new standard for teacher involvement. Every aspect of the innovation invited participation from the teachers and they responded admirable, becoming integral players in its evolution.

When the experiment in science education began in 1972, it was clear to the founding group that the teachers were the lowest rung in the education hierarchy. Within the classroom, they were the unquestioned fount of all knowledge to their students but the moment they confronted even the most insignificant authority in the education bureaucracy they became servile and submissive. The may have been considered part of the exploiting classes in the larger social order, but they were the exploited class within the school system, victims of their departmental officers, lacking in self esteem yet, ironically, forced to wear the mantle of omniscience in the classroom. So it was clear from the very beginning that educational change cannot occur unless the teachers were accorded respect and the honourable status that is their due. That was a ground condition.

These concerns shaped the HSTP’s interactions with the teachers. Most importantly, a serious attempt was made to create an official teachers’ forum that could give an honourable identity to the teaching profession and allow the teachers to conduct an ‘educational dialogue’ on wider philosophical and pedagogical issues, apart from discussions on their working conditions.

Arguably, the HSTP’s impact was unprecedented in the Indian context. Its influence on contemporary thinking in education and its imprint on the education system are clearly evident today. Not only did it highlight the vast array of possibilities for educational change, it also pioneered a path for change, showing how each separate aspect of the process can be implemented and sustained.

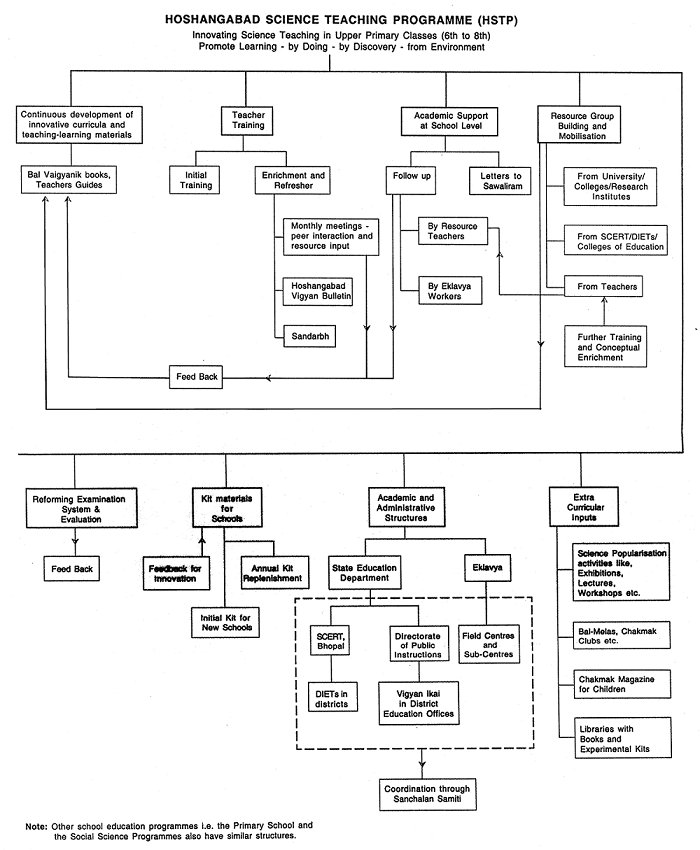

The HSTP viewed intervention as a multi-pronged process requiring simultaneous action on many fronts. Tinkering here and there was not enough; that was clear from the outset. All academic aspects of the teaching-learning process were addressed, beginning with the teachers actively participating in developing the curriculum. A kit for conducting experiments was put together to go with the new workbooks that were being written.

Another important component was teacher training, which we have referred to earlier. In addition, an institutional framework under the name of ‘Sawaliram’ was set up to answer the flood of questions from the children, whose curiosity about their environment was aroused by what they were learning. A decentralised system of follow up to schools was also put in place to help the teachers in the classroom and to collect feedback on how the innovation was being implemented in the field.

The examination system went through fundamental changes to free it of the tension it usually generated in the minds of the children. New ways of assessing what the children had learnt were introduced, the emphasis shifting from testing for rote learning and memory recall to assessing the development of conceptual understanding and experimental skills.

The HSTP can also be seen as the first instance of an intervention for educational change in the government school system conducted by an agency other than the state education department. It was a fresh breeze that shook the foundations of a moribund system and sought to rid it of its ‘educational inertia’.

Not being tied to the education department hierarchy was a decided advantage. So was the virtual absence in the HSTP group of people formally trained in ‘education’. This allowed the HSTP to establish an equation of equality at all levels among those interested in education and change.

The HSTP created and consolidated a framework of decentralised structures for its implementation, breathing new life into concepts such as the school complex and sangam kendra enunciated in the 1964-66 Education Commission report (Kothari Commission). It also helped to weaken the stranglehold of officialdom over the teachers while adding an academic dimension to the administrative apparatus.

The HSTP was a singular experiment in India’s education scenario and a source of inspiration for other initiatives across the country, adding new facets to the dialogue on education. The purpose of this volume is to recreate its aura by presenting its academic and administrative contributions in an organised and structured manner.

We discuss three main components of the HSTP in the book:

- Content: development and structure

- Teacher involvement: groundwork and inputs

- Examinations and student evaluation

Content includes syllabus, science topics covered, workbooks, kit for experiments, etc. This book seeks to trace the process of content development, choice of topics/concepts and their periodic revision. While clarifying the rationale behind the changes and the factors influencing them, we shall also try to explain how the content was structured in the framework of the syllabus.

We have also outlined different aspects of a prototype chapter to introduce the reader to the Bal Vaigyanik workbooks. These aspects are discussed in detail, after which a synopsis of all the chapters from the three Bal Vaigyanik editions published to date is presented. To understand how these chapters evolved, we have analysed the lifeline of three chapters in a chronological framework.

The Bal Vaigyanik showcases several dimensions of the teaching-learning process. We have included a brief chapter outlining our field experiences in preparing and using a series of teacher’s guides to help the teachers understand these processes.

We also present a brief discussion on the development of the kit to conduct experiments in the classroom, which is another important component of the HSTP. One of the concerns often expressed about experiment-based learning is that the requirement of a laboratory and kit makes it an expensive proposition. We examine the validity of this concern and discuss our attempts to make the kit more versatile and viable cost-wise, a process which saw contributions from scores of teachers and other volunteers.

As we have repeatedly pointed out, one of the hallmarks of the HSTP was its intensive interaction with the teachers. We have devoted one chapter to detailing our experiences in this area, tracing how teacher involvement and participation grew to become the innovation’s most important component and detailing the different forms this interaction has taken.

We next discuss the issue of educational materials and their use in the reality of today’s school environment, the focus being on our experiences with the kit for conducting HSTP experiments. The main source of data for this chapter is the periodic feedback reports filed by members of the HSTP resource group and follow-up group of their follow-up visits to schools. Information gathered from oral interactions with the teachers and written teacher reports has also been incorporated.

The final discussion in the book is devoted to the examination system – one of the most sensitive aspects of our education system. Apart from giving a detailed explanation of the changes in evaluation and assessment introduced by the HSTP, we also present an analysis of our actual field experiences in conducting examinations for middle school children.

UNDERSTANDING THE HSTP CURRICULUM AND SYLLABUS

In this chapter we shall examine the theoretical aspects of the HSTP curriculum and syllabus. To begin with, it would be wrong to assume that the innovation was launched with any clear-cut understanding of pedagogy and educational theory. Rather, as the work in the schools progressed and the understanding of teaching-learning processes grew, the theory underpinning the HSTP gradually emerged, gaining shape and substance. The entrenched belief was that theory emerges from practice so it was clear from the outset that understanding would evolve and develop. So it is fruitless to try and understand the HSTP and its underlying theory by pigeonholing it in any existing school of pedagogical thought.

One thing was clear from the beginning: ‘information’ could not be the foundation on which to develop the curriculum, given the ‘knowledge explosion’ we are witnessing in modern times. It was obvious that is impossible to incorporate this exponentially growing body of information into a curriculum. There was another serious limitation. Even if a curriculum managed to cover all the existing information at a given point in time, the children would find the information dated and probably even irrelevant 10 years down the line. That’s why the emphasis was on self learning. But the group knew this would be a slow and painstaking process because the child would be a participant in the journey..... Read More... [PDF 613 KB]

INNOVATIONS: LAYING THE GROUND FOR TEACHERS’ PARTICIPATION

Teachers played a central role in the HSTP. This was expected and necessary in a discovery-based teaching-learning method because the open-ended nature of the approach meant that a chapter could follow different paths in different classrooms. One could never really predict the questions children would ask or what would happen in the classroom. So the teacher had to intervene at every step to weave children’s questions into the learning process without derailing or altering its course.

In traditional classrooms, the role of a teacher is limited. (S)he is only expected to explain what is written in the textbook. At most (s)he can supplement the explanation with examples or analogies. So teaching usually means reading the textbook to the children and dictating answers to questions once the chapter is completed. Read More... [PDF 616 KB]